Kathleen Krull is an esteemed figure in children’s literature. Her books for young readers are fixtures in school curriculum and appear on countless awards lists and bookshelves. I had the honor of working with Kathleen on many books at Harcourt Children’s Books. For DearEditor.com’s 2012 Revision Week, I interviewed Kathleen to explore her revision process. Last Friday, the children’s books world lost this amazing talent, and I lost a dear friend. In Kathy’s memory, I repost that insightful interview.

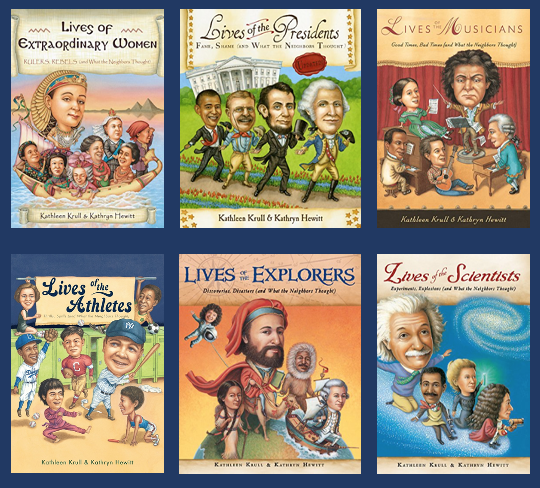

Kathleen Krull has written over a hundred books for young readers, most of them nonfiction. Among her most beloved books are Harvesting Hope: The Story of Cesar Chavez and the Lives Of series, which are collective biographies featuring 20 fascinating historical figures in each volume and stunning portraits by Kathryn Hewitt. To me, the Lives Of subtitles capture Kathleen’s lively approach to nonfiction:

- Lives of the Athletes: Thrills, Spills (and What the Neighbors Thought)

- Lives of the Scientists: Experiments, Explosions (and What the Neighbors Thought)

- Lives of Extraordinary Women: Rulers, Rebels (and What the Neighbors Thought)

- Lives of the Pirates: Swashbucklers, Scoundrels (Neighbors Beware!)

I had the honor of working with Kathleen on many of the Lives Of books, as well as other books at Harcourt Children’s Books. For DearEditor.com’s 2012 Revision Week, I interviewed Kathleen to find out how she revised her stories. Her answers give us a glimpse into one writer’s process, but more than that, they open up possibilities for improving our own processes. I share that interview with you today.

When you write a new picture book manuscript, how many drafts does it typically take before you’ll show it to an editor?

From the days when every penny counted, I’m so cheap with paper that I don’t print out a draft after I make every little change, so it’s hard to say. I print at least 10 to 15 drafts, representing what seem like substantial changes, before I’m happy. When I get to the point of taking out commas and putting them back in again, I feel ready to send it off.

How much revising happens after the editor sees that draft?

A lot, as you know, Deborah, from sitting across the desk from me once upon a time. A good example is Harvesting Hope: The Story of Cesar Chavez. True story: between what I thought was my final draft, and what emerged after the editorial process, only one sentence stood intact: “Grapes, when ripe, do not last long.” It’s not that I deliberately send in something unpolished, it’s that editors are indispensable. (Note from The Editor: Kathy gave me permission to take credit for coming up with the “Harvesting Hope” title. Kathy’s other wonderful editor at Harcourt, Jeannette Larson, was the primary editor on this book.) Watch the National Endowment for the Humanities book trailer for Harvesting Hope here.

You’ve started co-writing with your husband, author/illustrator Paul Brewer. How does that collaboration work?

It’s truly a collaboration. One of us will start with an idea (Fartiste, needless to say, was his), a paragraph, or a first page, and we’ll then pass drafts back and forth, endlessly tweaking. Paul specializes in research. With Lincoln Tells a Joke, he found all the jokes. Same thing with our upcoming funny book about the Beatles. (The Beatles Were Fab (and They Were Funny.) My focus is the final fine-tuning of the words. He typically works at night and I work days, so I’ll hand things off to him at the end of the day and find it back on my desk the next morning.

Did you use Paul or other critique partners for the books you wrote solo in the past?

Paul is usually the only one I show manuscripts to, for the simple value of watching his face as he reads. I can tell when he gets hung up, confused, or amused, and I use those reactions as clues when I’m revising.

Do you ever read your picture book manuscripts to kids to test them out?

I’ve tried this, but haven’t found it that helpful. I lean toward the “too many cooks” theory, that my views and the editor’s (and sometimes Paul’s) are what matter. More input than that can be muddling.

Can you share an experience of having a story problem you didn’t think you could solve but eventually did?

With my biography of Dr. Seuss (The Boy on Fairfield Street: How Ted Geisel Grew Up to Become Dr. Seuss), I found it flummoxing that his life, from all outward appearances, was pretty darn charmed. I like to write about obstacles overcome, battles fought and won, and with him the more I researched, the less conflict I found. After many, many drafts, I was finally able to tease out the theme that fooling around with words and pictures was not considered appropriate for an adult—but he did it anyway.

What’s the most drastic thing you’ve done to a story while revising?

With Fartiste, Paul and I tried every which way to tell the story of Joseph Pujol, a real French performer whose entire act was farting on stage. Nothing clicked until I hit upon telling the story in rhyme. Paul thought this was a terrible idea—among other reasons, most editors hate stories in rhyme. But then I came up with a few funny verses, and we were off and running. I’d like to use this remedy again, but it would have to be the right subject.

How do you know you’ve got the final draft?

When the editor and I have wrestled it into a story that seems to have written itself—that’s the goal anyway.

Thank you all for reading. I hope you enjoyed this glimpse at how Kathy worked her magic. While I miss my friend terribly, my heart soars knowing that her books will continue to enlighten, entertain, and inspire.

*Some books Kathleen published after this interview: Joey: The Story of Joe Biden (with Dr. Jill Biden), Starstruck The Cosmic Journey of Neil DeGrasse Tyson and, No Truth Without Ruth: The Life of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Also, check out the book trailer for her upcoming Walking Toward Peace: The True Story of a Brave Woman Called Peace.

**To read more interviews about revision, go to the Revision Week Interviews Archive.